Brian Wesbury, one of my favorite economists, recently spoke about the supply chain shift that seems to be happening right now in China. Wesbury used an informative analogy of the UK and Japan and their respective economies during the 1970s and 80s.

Wesbury’s bottom line is that real innovation comes from a free-market economy, and innovation sustains continued growth. This point is true because, unlike government-dominated economies, free markets can pivot easily in new and different directions as times change.

Conversely, economies with a top-down economic system (where the government largely controls the direction of the country’s economic activities) perform far worse than their free-market counterparts in the long run. This is because they are more rigid and lacking in true innovation.

Let’s dive in.

After World War II, the western world came to believe that big business, big banks and big government all coming together is what won the war. Remember, the joint effort of massive airplane and tank production is what arguably overwhelmed the Axis powers. This new mindset shaped economies in the coming decades.

If we consider the differences between how the UK and Japan each handled their respective economies post WWII, we’ll see an important distinction.

In the 1970s, the UK government was the entity that essentially picked coal and steel as their economic focus. These were the industries that they decided to subsidize and push. So, in essence, the government chose the financial roadmap of the country, thereby overpowering a free market system. In the years to come, the economy in the UK was sluggish at best.

Now, during the same period, Japan’s government did the same thing, only they settled on very different markets. They picked consumer electronics – think camcorders (do they still make those?), cameras, VCRs (same question), automobiles, motorcycles and the like.

By the 1980s, the world had come to believe that Japan had the secret to national economic success. The world also thought the Japanese had figured out the best way to run just about any business. This “truth” was so accepted that American business schools frequently assigned textbooks detailing Japanese management techniques.

And, indeed, for many years, Japan was a world leader in economic world power, besting the UK by miles.

The divergent paths of the British and Japanese economies were the result of top-down decisions. But candidly, Japan just got lucky. They happened to pick the right goods and the right industry for growth – electronics was a better choice than coal and steel.

But, when it came time to pivot, and move on and away from electronics, Japan got left in the dust. The country got stuck selling merchandise in Radio Shack, Comp USA, and Circuit City. And we all know what happened there. Remember Comp USA? It was founded in 1985 and was defunct by 2012.

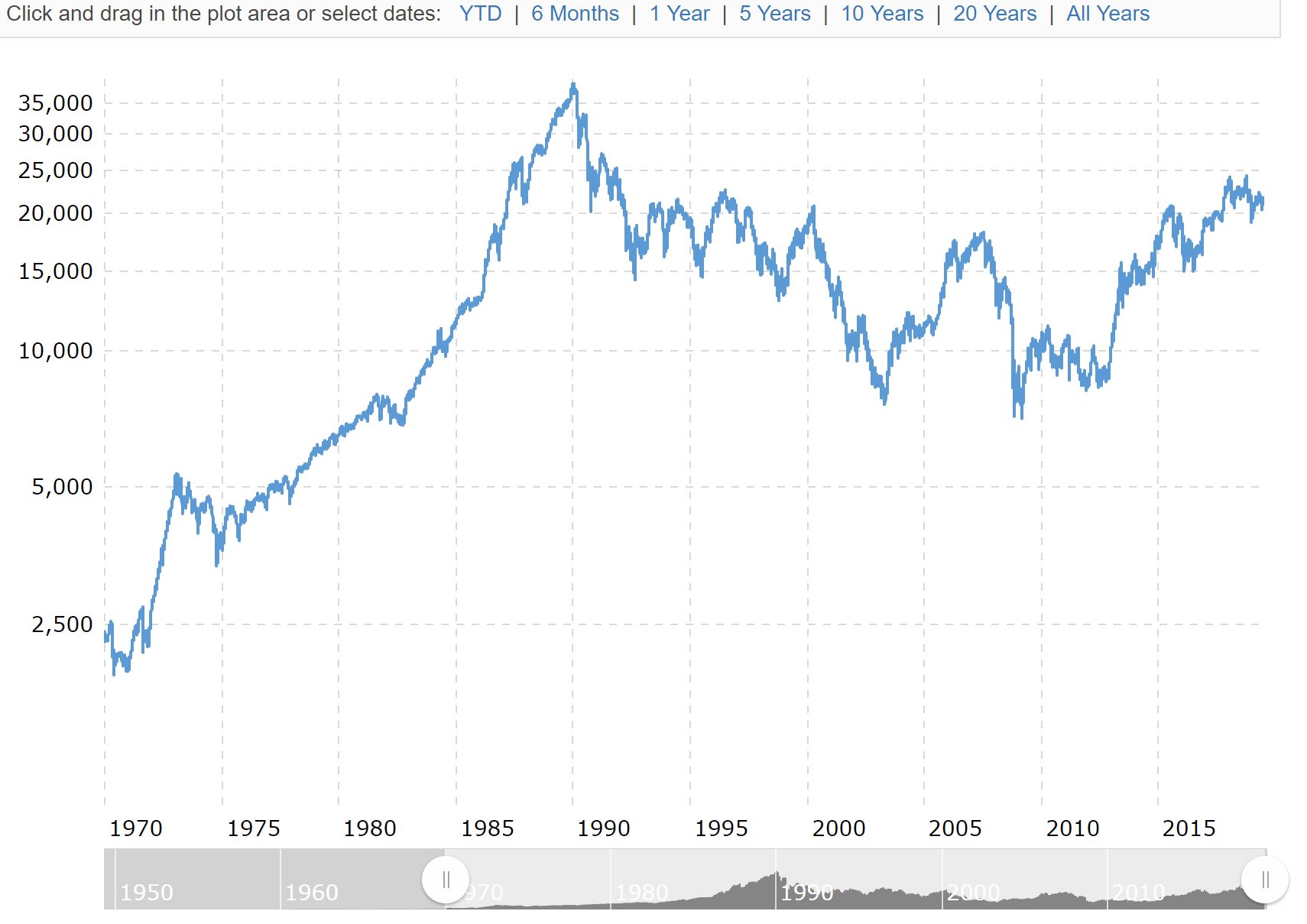

Nikkei 225, or the Japanese equivalent of the S&P 500, rocketed from 2500 in 1970 to 38,000 by 1989. But in that year and the next, the world economy started to leave Japan behind. The Nikkei fell to under 8000 in 2009. Today it is hovering at just 20,000. That’s a full 18,000 points below its glory days.

Take a look at this chart that depicts the movement of the Nikkei over time:

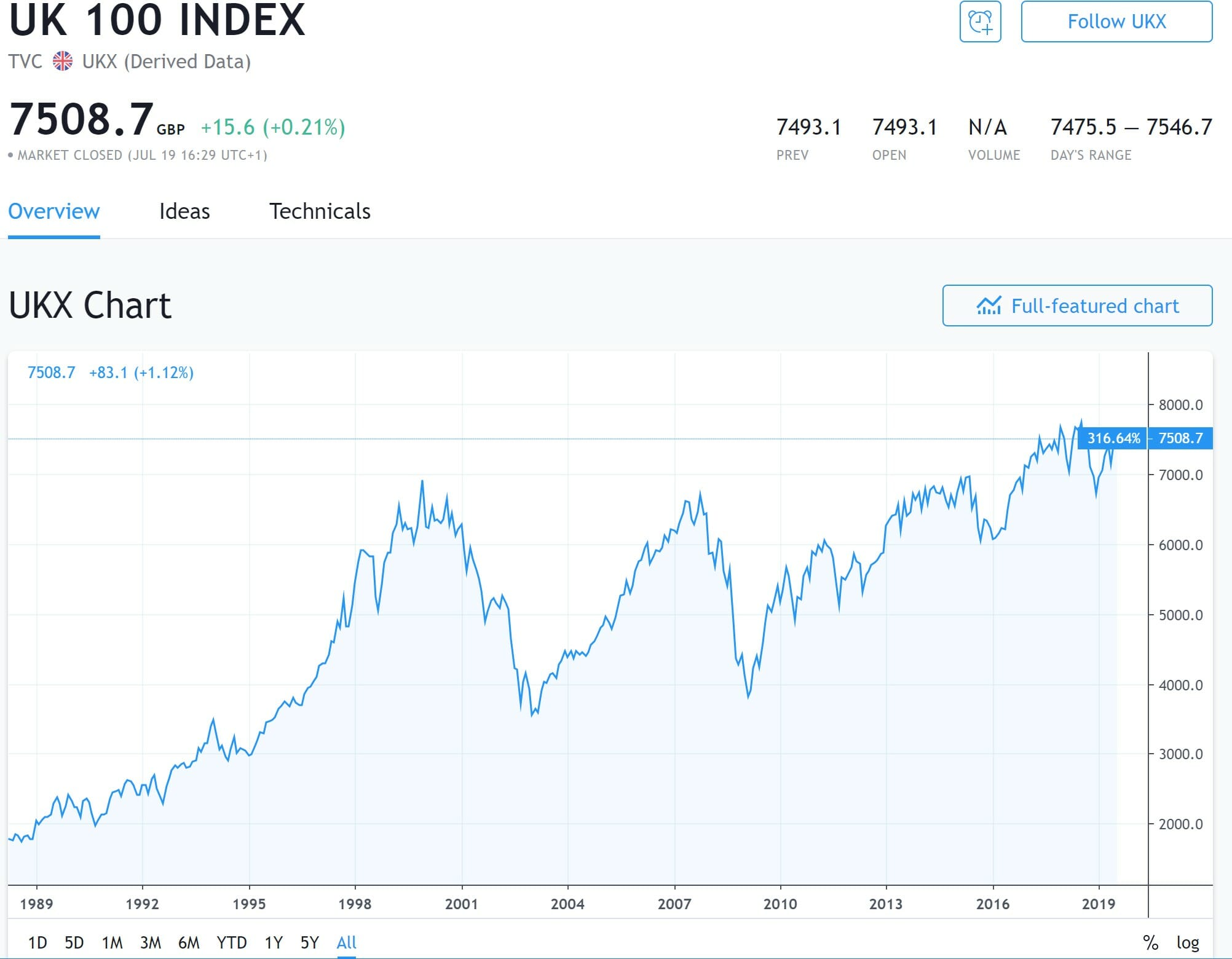

While Japan stayed its top-down course, the UK smartly decided to implement a free market economy. Under Margaret Thatcher, the UK was able to smoothly transition to this new system, which brought increased innovation and a renewed period of growth.

Herein lies the moral of our story. Top-down economic systems rarely thrive for extended periods, and there is a bit of a guessing game involved. It’s analogous to time-in-the-market versus timing the market; it’s difficult to choose which industries will soar and which will crash and burn. So, over the long term, a free market economy wins out because it fosters innovation and technological advancements, and these are the key ingredients to real growth.

Turning the focus to modern-day China, they are growing at 10% after decades of inertia. We all know that China’s government has allowed the country’s businesses to steal American intellectual property (IP) and our technologies. This practice is government-sanctioned and supported. To add insult to injury, China then exports lower cost goods to rev its national economic engine further.

But China is running out of room to grow, just as Japan did in the 1990s, and it’s problematic for them to pivot now. The country is well-known as a top-down economy and the leader in cheap exports of lower-value goods. Think of China as a can opener nation; their bread and butter are clothing, plastic, low-cost furniture, electrical equipment, and computers. (Sounds like Japan, right?)

China doesn’t encourage innovation or growth. This is starkly apparent when we compare it to the free market economy here in the US.

Sure, the trade war and tariffs are putting pressure on China to make a pivot, so China has to come to the negotiating table. Companies are leaving China in droves. Primarily, China is losing supply chains, and these are like the central nervous centers of businesses. And, once they go, they don’t come back.

This shift is what we call the global rebalancing of a free market that adapts.

According to the Washington Post, more than 50 multinational corporations have announced plans to move manufacturing out of China. Google, Nintendo, and Dell, among others, are attempting to avoid the import penalties on $250 billion of Chinese goods. But rather than move their operations to the US (as President Trump has urged), many of these companies are aiming to rebuild their supply chains abroad, primarily in Southeast Asia.

As examples, video game giant Nintendo plans to go to Vietnam and has already diverted production of the popular Switch console to Vietnam. Google has plans to move manufacturing of its Cloud motherboards and some Nest smart home products to Taiwan and Malaysia. And, Hewlett-Packard is relocating significant parts of their personal computer manufacturing to other countries in Southeast Asia.

Apple is also evaluating the cost of moving 15% to 30% of its production out of China. This move would represent a transition away from the company’s largest international market, where it has anchored manufacturing for the past 20 years. Because of the mounting manufacturing risks in China, Apple is suspected to shift out of the country – whether a trade agreement is reached or not.

A July survey from the Quality Control & Supply Chain Audits (QIMA) indicated that demand for China-based inspections from US companies had fallen a staggering 13% in the first half of 2019. During that same window, the overall demand for inspections in South Asia ballooned to 34 percent.

The take away: government-directed economies don’t work for long, but free markets do. Our economic system, which fosters innovation, technology, and growth, works for us Americans, and it works well. And, it should continue working and growing for decades and decades to come.

1 Comment