When interest rates go up, investors often worry that higher interest rates could jeopardize economic growth. This year, the Federal Reserve has hiked short-term rates three times, raising its key rate in the 2% to 2.25% range.

So should we be nervous? I don’t think so.

We enjoyed a long period of historically low rates in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. Now, against the backdrop of a solid domestic economy, with many key indicators pointing to continued expansion, the Fed is reacting by returning borrowing costs to more “normal” levels.

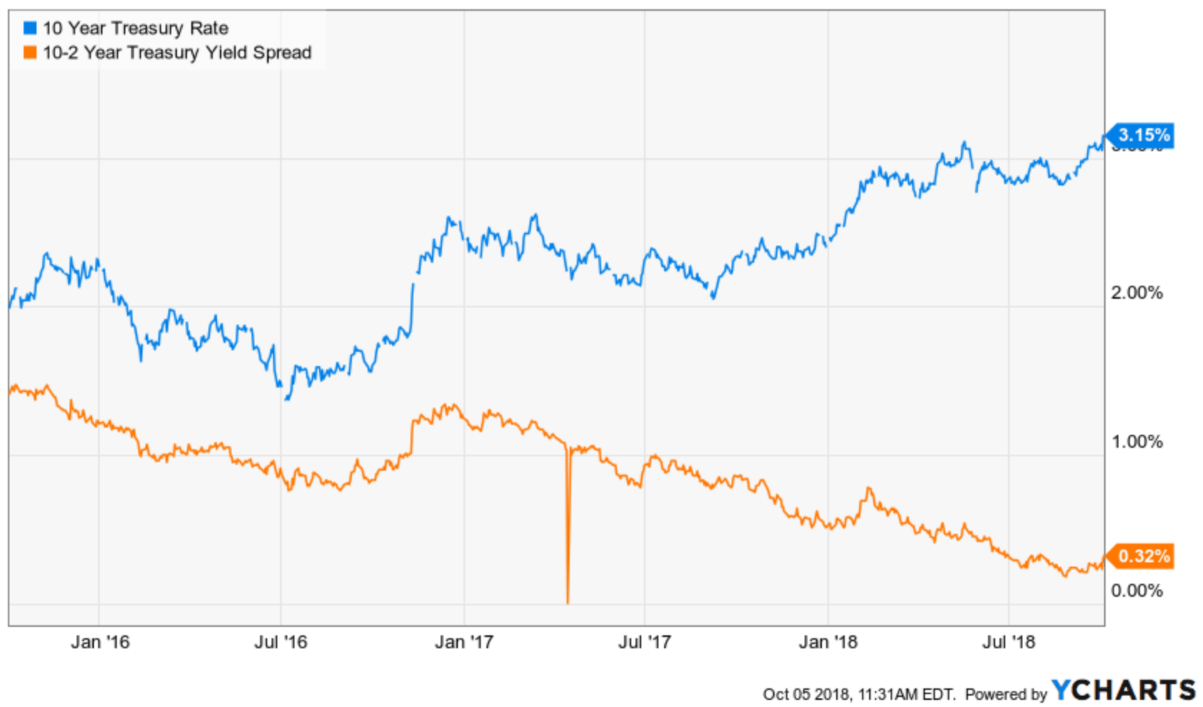

In 2016, the benchmark 10-year Treasury note (10YR) yield touched 1.3%. That rate has more than doubled to its current 3.2%. But we can’t just look at pure numbers when assessing the impact of higher rates. We’ve got to consider the context. One of the most important pieces of contextual data to factor is the yield curve.

A “yield curve” is a visual description of what bonds should pay at various maturities – they’re what you get if you plot bond yields along a timeline for one, two, five, ten and 30 years and connect the dots. The line is supposed to slope up, meaning you should get more interest the longer you tie up your money. So, 30-year yields should be higher than ten, ten higher than five, and so on.

When the yield curve becomes inverted, we may be in the danger zone for recession. That’s because, over time, inverted yield curves have proved a pretty accurate signal of economic trouble. The real indicator comes when we take the ten-year yield and subtract the two-year yield. Normally, this is a positive number, as the ten-year number should be higher than that of the two-year. Imagine 3% for the ten-year and 1% for the two-year. Here, we get positive two. That’s good stuff.

Today, our yield curve is better than it was over the last few weeks. The ten-year is near 3.25%, and the two-year is at about 2.8%. We started the year with the 10YT at 2.4%. So, if the 10YR had not risen, the yield curve would have inverted. But, rates have moved higher across the board. Currently, there is more of a cushion than when we wrote about this in late summer, when the 10-2 Year Treasury Yield Spread was 0.18 – dangerously close to zero. Today this figure is 0.35.

The bottom line is that these rates and the difference between them are worth watching, and we will continue to do so.

The recent hike is only problematic if you have owned long-term bonds, like the Vanguard BLV, which is down 10 ½ % YTD in price, but less if you count the coupon. If you’ve owned short-term bonds this year, however, you’re basically flat, landing at anywhere from down 1% to up 1%. This is not great news, but that’s the point of owning the right kind of bonds for a rising rate environment. And, understanding that a bad year for bonds can happen in a day for stocks.

My bottom line on bonds is that I’m still okay owning them – short-term or even individual bonds that have a set maturity date – while we ride out the rate-rise storm.

As for stocks, we saw a big stock sell-off last week as rates spiked. Still, wage inflation remains under 3%. Stocks don’t love rates jumping up on any given day, but over time there’s a direct correlation between rates rising on the 10YT and stocks going up, at the same time, until the 10YT gets to 4.5%, and wage inflation gets to 4%. For both of these things to happen, we have a long way to go.

We know that, as a general rule, rising rates slow the economy. But, as long as rates and wage inflation are in a moderate place (which they are), stocks still have a decent backdrop.